A psychoanalytic movement recently offered an intriguing seminar interrogating whether "we are all delusional here?"

The colloquium was indebted to Lacan's musings about James Joyce, who may, or may not have avoided some devastating psychosis by novel-writing and word playing. Nevertheless asking whether "we" are all mad "here" predated both James Joyce and Jacques Lacan.

But I don’t want to go among mad people," Alice remarked.

"Oh, you can’t help that," said the Cat: "we’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad."

"How do you know I’m mad?" said Alice.

"You must be," said the Cat, "or you wouldn’t have come here.”

― Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

Occupants of Wonderland are by definition "mad"; but each in their own way. The Hatter is mad, though in a different way from the Red Queen.

Whereas the English language attempts some differentiation between illusion and delusion; continental French prefers the word Illusion which embraces both concepts and all degrees of the same. So one can reform Lacan's question to read whether all human subjects are immersed in some illusionary version of reality. If one wanted to talk about the delusions encountered in psychiatry, the choice words would derive from a variety of word. One of the greatest French diagnoses of the early twentieth century was "la folie des grandeurs" or in English "delusion of grandeur"

Interrogating psychosis is a cultural undertaking of venerable age. How and why do people with seemingly psychotic symptoms abruptly cease they display? One possibility highlighted by some, is that a more stable existence might be acquired by pursuing a hobby -like writing or art. Such a hobby is not simply a conduit for excessive thoughts, feelings, or energies. Nor is it simply a new dawn of creativity. Rather deep commitment to a creative hobby helps individuals to stabilise themselves socially, psychologically, and culturally.

Unfortunately there have been people living within the structures or styles called psychosis who had hobbies, professions, meditations, and pursue keenly cultural endeavours; but nevertheless fail to stabilise. On might recall Lucinda Joyce. The promising avant garde artiste who was a promising, creative dancer, failed to make a career even with help from C G Jung and a succession of psychiatric experts. The Irish choreographer and historian of dance, Deirdre Mulrooney, wrote

Not unlike Mary Wigman, founder of German Ausdruckstanz/Dance of Expression, after a few broken engagements, Lucia suffered a nervous breakdown. While Wigman survived her breakdown to become one of the most important modern dance practitioners of the 20th century, Lucia was incarcerated by her brother, and ended up trapped in mental asylums for most of her life, with many equivocal diagnoses, variously put in straitjackets, and once even injected with bovine serum. (Giorgio Joyce, quite a tragic figure himself, would also commit his ‘marvellously wealthy’ older wife Helen Fleischmann to a mental institution). Alas, Lucia’s father, her greatest champion and supporter, died when she was just 34. After his death, Nora never visited Lucia again. Giorgio only visited her once, in 1967. Go figure! Lucia outlived them both, until 1982, in Saint Andrew’s Mental Asylum in Northampton.

See: Reclaiming Lucia Joyce's legacy - The Lyric Feature

https://www.rte.ie/culture/2019/0711/1061493-reclaiming-lucia-joyce-the-lyric-feature/

The distinction -whether structural or no- between florid psychosis and ordinary living enjoys an extensive practical history.

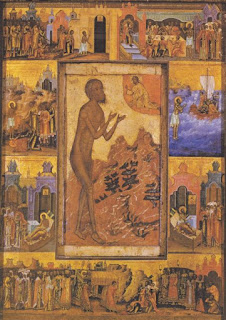

In the history of European medicine, the greatest theorist of "melancholy" was the scholarly academic Richard Burton. He offered several typologies for melancholia: love depression is one, whilst religious mania was another. Russia, for instance, enjoys a proud history of holy fools One called Basil was

Naked, dirty & forever mumbling their prayers, they could proffer raw meat to a tsar, call him a bloodsucker and yet still be invited to a royal feast afterwards. Their “supernatural” powers inspired awe in nobles and peasants alike.https://www.rbth.com/history/331573-why-did-russian-tsars-love

holy icons of st basil: fool of christ

Another question begging answers is the location and identity of the "we" in this quote. Most concepts relating to identity or location are slippy. A valued colleague suggested to me how an innocuous everyday "we" can easily become a big or royal WE. Any therapeutic practitioner talking about a "we" - is referring to a bigger Other. This "we" thus resembles claims made by religious, political, and other social groupings when isolating a sanctioned authority along with an excluded minority. resembling somewhat the "cart and carriage" or "love and marriage. The we lends me an identity which nobody can tarnish, because the "we" of the Others is inviolable, absolute, and indubitable. Theories of religion refer to this epistemic style as "fideism". It is a near absolute claim, encapsulating the All and the Others in a god, political belief, praxis, or imaginary group structure.

Testifying about one's psychoanalytic experience obviously concerns chiefly my own experience, social being, history, including even my amazing professionality. But how can others be expected to ratify it?There is a circularity here when traversing from I to the We, thence to the Others and back again to myself. It resembles a solipsist wondering why there aren't more people that agree with her. Maybe it is easier to shut the discussion down because some allegedly foundational concept is being attacked. Fideism is a conundrum that creates and destroys its own truth and testimonies.

Everything I claim to be the case is- eo ipso- related to everything else. Hence my subjectivity is valid for all.... just as all Lacan's concepts are related internally as well as chronologically

Criticising Lacan or Freud is supposed to be both futile and contradictory. One is better to subjectivise their teachings. Interrogating writings from some futile "external" viewpoint means one is metamorphosed into an academic, philosopher, master, or super therapist. This position is reified. I cease being a Subject Viator -always in transit. Now I have arrived at my destination and destiny. Nevertheless it is sometimes imperative to interrogate. For example many speakers at the conference mentioned above thematised the concept of delusion. They teased out differences between psychosis or the "psychotic" by exploring regional ontologies for delusion. Hence one might be exceedingly delusional, without necessarily adopting a full-blown psychotic style.

During the first fifty years of the twentieth century it seems to me that most behaviours, specialisms, and institutions devoted to "the psychotic" were obscured, if not downright hidden from public interrogation in western civilisations. As the century proceeded psychological, analytic, and psychiatric words became more widely known and used, whilst pseudo-illnesses (such moral insanity, homosexuality, along with supposed perversion, degeneration or stigmatised minorities).

Eventually concepts of mental illness became banal during the following century. From the nineteen sixties onwards "mental health" came to refer to an increasing public awareness of a previously hidden sector of society. I remember well when I began to work in the domestic department of one of the largest psychiatric hospitals in Europe as a stores labourer. The director of the hospital said to me at interview "I have some massive wards here that will terrify you". He predicted correctly; because he was referring to vast "psycho-geriatric wards" that shocked a boy of seventeen. They reminded me of the black and white

holocaust documentaries produced after the defeat of Germany and her allies that accompanied most of my childhood.

holocaust documentaries produced after the defeat of Germany and her allies that accompanied most of my childhood.

A young boy walking along a roadside strewn with corpses in Dachau. Copyright Getty & also public domain

As novelist Beryl Bainbridge testified, the war was indeed over but the nightmares were just beginning.

WE WERE never taught about the war at school. Because my father's business friends in Liverpool were mostly Jewish, I actually believed that the war was being fought to save the Jews. I couldn't have been more wrong.

When the war was over we went to the Philharmonic in Liverpool. We got out of the train at Exchange station, then walked in a crocodile to the Philharmonic Hall in Hope Street and saw the films the troops had taken when they entered Belsen.

It was the most extraordinary, numbing experience - those little mummified skeletons which were just being pushed up by a machine, to be carted into pits ... I had nightmares for a long time afterwards. Independent Monday 08 June 1998

Whilst many of my colleagues rightly explore the meaning and structures of delusions, my purposes here are more modest. I am interrogating the "we" and the "here" associated with the quotation about delusion.

The "here and now" of delusions that followed public images after the "Shoah" which incinerated innumerable Jews, communists, gypsies, and gays, has poignant currency still. Were Europeans delusional or even mad to inflict such destructiveness on themselves and their Others -even after the previous destructions of 1918!! The "now" can contract and expand its magnitude as required by its users. But I doubt it is a definable temporal concept because of its slippage and diverse composition of ideal, real, and fantasy formations.

Hence the "We" contracts and expands. During Bainbridge's paragraphs the "we" is a family, one's school pals, an educational establishment, a religious/ethnic minority, and business associates. But it expands in time, in space.

icon of basil